Adobo is considered the Philippine national dish, which basically means that in a country of 7000-plus islands, three geographic regions, 186 local languages, and many ethnic groups, adobo is the one dish most commonly found in kitchens throughout the country. Essentially adobo-style cooking involves braising, usually chicken or pork, though fish, squid, and vegetables work too, in a vinegar, garlic and black peppercorn sauce. Though Filipinos like to claim that their version of adobo (or more precisely, their mother's or lola's adobo) is the best, they concede that there are as many variations on the basic vinegar sauce as there are cooks in the country. Home cooks and restaurant chefs alike use any or all of the following seasonings depending upon regional and familial tastes: soy sauce, fish sauce, ginger, coconut milk, sugar (sometimes refined, sometimes brown sugar), chili pepper, and bay leaf. I read one blog commenter who said her family always uses Sprite, and a friend recently mentioned that he's heard of Coke as an adobo ingredient.

Consider this: if you've eaten any Mexican, Chinese, or Indian cuisine in the past week, your next dish may be Filipino food. Though the Philippines was a colony of the US for almost 50 years at the beginning of the 20th century, and Filipinos are currently the fourth largest immigrant group coming to the US--after Mexicans, Chinese, and Indians--Filipino cuisine is just now spreading in the US beyond the Fil-Am community and their close admirers : ) Mainstream food media, including TV cooking shows, magazines, newspaper columns, and online media are presenting more and more Filipino recipes to a wider American audience. It's no surprise, then, that adobo is being cast as the quintessential Filipino dish, the one to make.

Back in 2002, Mark Bittman included a chicken adobo recipe in his NY Times column. While the Food Network lists only nine Filipino-identified recipes on their website, of these adobo is by far the most popular. (Sadly, Emeril is the only programed chef who has featured a Filipino-identified recipe: Filipino-Style Wrapped and Deep Fried Bananas. What's up with that, Food Network?) America's Test Kitchen, the popular PBS food show and magazine, featured chicken adobo and food writer Sam Sifton took on the adobo challenge once again for New York Times readers in 2011.

As someone who has traveled for almost four months in the Philippines, eaten countless versions of adobo--from the excellent to the bland to the awful--and tried to make the dish myself--with results from the awful to acceptable--I'd like to suggest that Americans put a big hold on the push for adobo as the Filipino dish that white suburbanites in Tempe should make with three-fourths of a cup of soy sauce and a half a cup of vinegar because Mark Bittman said so.

At this point in culinary history, we can avoid a major adobo misstep if we act more carefully (see also: chop suey as "Chinese food;" hamburger broth spaghetti sauce as "Italian food;" and Old El Paso taco shells as "Mexican food.") Honestly, do we want 25 years of boring adobo in American malls food courts because white-bread Chris Kimball of ATK couldn't figure out the vinegar challenge of adobo and as a result said, "Let's just add coconut milk!"?

Pinoys and their allies need to stop the PR blitz that says adobo is just a humble and simple-to-make dish of the people. If you've really eaten a lot of adobo, and I mean other than your mother's, adobo made by other Filipinos even, you will realize that good adobo is actually very hard to find, much less make. Good adobo is a delicate balance between 1) the vinegar, faintly sour with bright notes that highlight 2) the protein or vegetable getting braised, and 3) the other seasoning or flavors of the dish (if there are any, such as soy sauce, coconut milk, etc.). The extra ingredients should never dominate the first two.

In my experience of eating adobo here in the Philippines, too often the vinegar is lost because the sauce has been cooked with too much heat or for too long. Or it's just watered down. What's left is a boring, uninspired adobo. Worse, and I've had this a number of times, the vinegar takes over and it's too pungent. It overpowers everything in the dish. This was the case of a chicken adobo I had at a fast-food joint in Manila called The Adobo Connection. The sauce was clumpy and well, fumey. Finally, if a cook adds too much ginger or sugar or soy sauce (Mark Bittman!), the vinegar and natural flavors of the food are lost. Good adobo strikes a delicate balance.

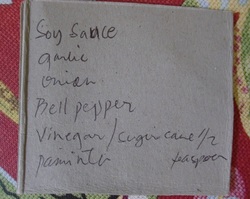

Last week, I tasted what a considered a really note-worthy adobo in a restaurant at a resort on Siquijor Island and I wanted the recipe. I sweet-talked the cook Janice for three days, and once the boss-boss, a Brit married to her sister, was out of ear shot, here's what she gave me:

Consider this: if you've eaten any Mexican, Chinese, or Indian cuisine in the past week, your next dish may be Filipino food. Though the Philippines was a colony of the US for almost 50 years at the beginning of the 20th century, and Filipinos are currently the fourth largest immigrant group coming to the US--after Mexicans, Chinese, and Indians--Filipino cuisine is just now spreading in the US beyond the Fil-Am community and their close admirers : ) Mainstream food media, including TV cooking shows, magazines, newspaper columns, and online media are presenting more and more Filipino recipes to a wider American audience. It's no surprise, then, that adobo is being cast as the quintessential Filipino dish, the one to make.

Back in 2002, Mark Bittman included a chicken adobo recipe in his NY Times column. While the Food Network lists only nine Filipino-identified recipes on their website, of these adobo is by far the most popular. (Sadly, Emeril is the only programed chef who has featured a Filipino-identified recipe: Filipino-Style Wrapped and Deep Fried Bananas. What's up with that, Food Network?) America's Test Kitchen, the popular PBS food show and magazine, featured chicken adobo and food writer Sam Sifton took on the adobo challenge once again for New York Times readers in 2011.

As someone who has traveled for almost four months in the Philippines, eaten countless versions of adobo--from the excellent to the bland to the awful--and tried to make the dish myself--with results from the awful to acceptable--I'd like to suggest that Americans put a big hold on the push for adobo as the Filipino dish that white suburbanites in Tempe should make with three-fourths of a cup of soy sauce and a half a cup of vinegar because Mark Bittman said so.

At this point in culinary history, we can avoid a major adobo misstep if we act more carefully (see also: chop suey as "Chinese food;" hamburger broth spaghetti sauce as "Italian food;" and Old El Paso taco shells as "Mexican food.") Honestly, do we want 25 years of boring adobo in American malls food courts because white-bread Chris Kimball of ATK couldn't figure out the vinegar challenge of adobo and as a result said, "Let's just add coconut milk!"?

Pinoys and their allies need to stop the PR blitz that says adobo is just a humble and simple-to-make dish of the people. If you've really eaten a lot of adobo, and I mean other than your mother's, adobo made by other Filipinos even, you will realize that good adobo is actually very hard to find, much less make. Good adobo is a delicate balance between 1) the vinegar, faintly sour with bright notes that highlight 2) the protein or vegetable getting braised, and 3) the other seasoning or flavors of the dish (if there are any, such as soy sauce, coconut milk, etc.). The extra ingredients should never dominate the first two.

In my experience of eating adobo here in the Philippines, too often the vinegar is lost because the sauce has been cooked with too much heat or for too long. Or it's just watered down. What's left is a boring, uninspired adobo. Worse, and I've had this a number of times, the vinegar takes over and it's too pungent. It overpowers everything in the dish. This was the case of a chicken adobo I had at a fast-food joint in Manila called The Adobo Connection. The sauce was clumpy and well, fumey. Finally, if a cook adds too much ginger or sugar or soy sauce (Mark Bittman!), the vinegar and natural flavors of the food are lost. Good adobo strikes a delicate balance.

Last week, I tasted what a considered a really note-worthy adobo in a restaurant at a resort on Siquijor Island and I wanted the recipe. I sweet-talked the cook Janice for three days, and once the boss-boss, a Brit married to her sister, was out of ear shot, here's what she gave me:

I know. Not much help really. I understand that Janice has her art and it can't be put into the confines of measured recipe. I get it. But it also reveals that Janice learned to make adobo by doing it repeatedly, adjusting ingredients by trial and error over the years. She adds ingredients without measuring and knows the delicate melding of acidic, savory and sweet flavors that she wants. Both the Times and ATK acknowledge that the balance of the vinegar and salty soy sauce is a challenge in adobo, but in both cases, they sort of cop out and throw in some coconut milk to temper the pungency of the acid problem. (Okay, admittedly Sam Sifton of the Times consulted Romy Dorotan of Brooklyn's Purple Yam who legitimately grew up in a region where coconut milk is a prominent ingredient in many dishes, including adobo. While it's nice Sifton's promoting Purple Yam, trust me, if you're cooking for a Filipina who grew up on non-coconut milk adobo and you tell her that yours has it, get ready for the eye-rolls and guffaws. Though Sifton explains Dorotan's regional take in the fine print, the food journalist should have named the dish more prominently--in the lede?--as a Bicol regional specialty, not simplifying the dish as broadly Filipino. Also, and maybe I'm harping too much, but if Sifton wanted a regional specialty from Dorotan, he should have gotten his recipe for Bicol Express!)

In order to save adobo from a horrible future as a fledgling newcomer to American cuisine, here are some suggestions:

1) Let's all acknowledge that good adobo is difficult. It takes home cooks generations of family guidance and for rookies it may take repeated practice. If authentic Filipino food is what you're after--and you're not Pinoy or have never actually eaten good adobo--maybe you should start with other dishes. Contrary to mainstream media's narrow offerings, there are many native Filipino or Fil-Am food bloggers writing about the diverse cuisines of the islands. With careful research, you can create dishes that allow for plenty of trial and error while still making yummy food. (Stay tuned--I'll share one recipe in a future post.)

2) Never make an adobo recipe that calls for more soy sauce than vinegar. Vinegar is the the important seasoning element and while it shouldn't over-power the dish, you should be able to taste it. There are regions that don't use any soy sauce at all, so keep this in mind. Use the soy sparingly.

3) Unless you're making Bicol adobo, be cautious of recipes that call for coconut milk. It is often promoted in recipes by the unknowing (uhum, white folk) who get scared by vinegar and other seasonings.

4) If you are up for the adobo challenge, here is a solid adobo recipe called Classic Chicken Adobo. And after my third attempt at adobo (the two previous attempts were lame), this one got my approval and more importantly, the approval of my Pinoy husband. The recipe has very basic ingredients and it originated from a legit Fil-Am food blogger (Burnt Lumpia) and cook book author Marvin Gapultos. It was posted with permission on the blog Serious Eats, though it first appeared in Gapultos cookbook, The Adobo Road.

I should add as a note to my own preparation of Classic Chicken Adobo: I took the chicken out of the braise after less than 30 minutes (Filipino chickens are smaller than American birds.) I added red chili flakes and some chopped fresh chili peppers. I also threw in vegetables (whatever I had in the fridge: onions, pumpkin, and green beans) to the sauce as I reduced it in the final 8 minutes. Though Pinoys traditionally don't do this, almost all recipes of pork or chicken in a sauce can handle vegetables added in. Meanwhile, in the final step, instead of broiling or roasting the chicken in the oven, I crisped the skin of the chicken thighs in a wok before re-saucing them and serving. Sarap!, as the locals say, Delicious!

In order to save adobo from a horrible future as a fledgling newcomer to American cuisine, here are some suggestions:

1) Let's all acknowledge that good adobo is difficult. It takes home cooks generations of family guidance and for rookies it may take repeated practice. If authentic Filipino food is what you're after--and you're not Pinoy or have never actually eaten good adobo--maybe you should start with other dishes. Contrary to mainstream media's narrow offerings, there are many native Filipino or Fil-Am food bloggers writing about the diverse cuisines of the islands. With careful research, you can create dishes that allow for plenty of trial and error while still making yummy food. (Stay tuned--I'll share one recipe in a future post.)

2) Never make an adobo recipe that calls for more soy sauce than vinegar. Vinegar is the the important seasoning element and while it shouldn't over-power the dish, you should be able to taste it. There are regions that don't use any soy sauce at all, so keep this in mind. Use the soy sparingly.

3) Unless you're making Bicol adobo, be cautious of recipes that call for coconut milk. It is often promoted in recipes by the unknowing (uhum, white folk) who get scared by vinegar and other seasonings.

4) If you are up for the adobo challenge, here is a solid adobo recipe called Classic Chicken Adobo. And after my third attempt at adobo (the two previous attempts were lame), this one got my approval and more importantly, the approval of my Pinoy husband. The recipe has very basic ingredients and it originated from a legit Fil-Am food blogger (Burnt Lumpia) and cook book author Marvin Gapultos. It was posted with permission on the blog Serious Eats, though it first appeared in Gapultos cookbook, The Adobo Road.

I should add as a note to my own preparation of Classic Chicken Adobo: I took the chicken out of the braise after less than 30 minutes (Filipino chickens are smaller than American birds.) I added red chili flakes and some chopped fresh chili peppers. I also threw in vegetables (whatever I had in the fridge: onions, pumpkin, and green beans) to the sauce as I reduced it in the final 8 minutes. Though Pinoys traditionally don't do this, almost all recipes of pork or chicken in a sauce can handle vegetables added in. Meanwhile, in the final step, instead of broiling or roasting the chicken in the oven, I crisped the skin of the chicken thighs in a wok before re-saucing them and serving. Sarap!, as the locals say, Delicious!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed